The Turtle Hospital

Back in September, Arthur and I spent a few days camping at Bahia Honda State Park in the Middle Keys. One afternoon we took a break from snorkeling to visit the remarkable Turtle Hospital on Marathon.

Welcome to The Turtle Hospital

The Turtle Hospital has an interesting history. Here is a brief overview (related from signage at the hospital; any factual errors are mine).

It started when a man named Richie Moretti purchased Marathon’s Hidden Harbor Motel in 1981. The hotel had a 100,000 gallon saltwater pool, which was converted to display fish starting in 1984. The following year, local schools started visiting the hotel pool for marine education programs. Students asked, “where are the turtles?” Good question!

In 1986, Moretti obtained a permit to rehab sea turtles. The first patient arrived at the facility, now named the Hidden Harbor Marine Environmental Project, that same year. More patients arrived. Surgeries would be performed in re-purposed motel rooms.

The facility expanded in 1991 when the nightclub next door to the motel was purchased. The nightclub became The Turtle Hospital in 1992.

Turtle ambulances

In 2005, Hurricane Wilma hit the motel and hospital hard. Flooding to the property was extensive and the motel ceased operation. The entire facility registered as a non-profit organization and continued as a rehabilitation center and turtle hospital. Today, the motel rooms are used (in part) for storage, and to house interns, visitors, and staff.

There’s no doubt the facility used to be a motel!

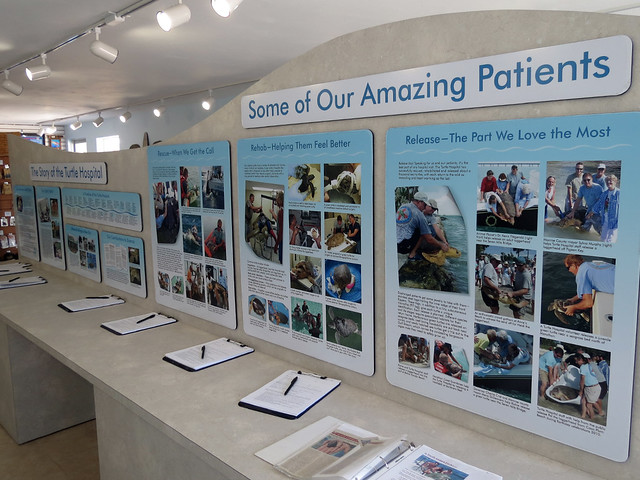

In 2010 a brand new education facility, funded by the Florida Sea Turtle License Plate, opened at the hospital.

Life-size models of sea turtles

Lots of turtle information in the education center

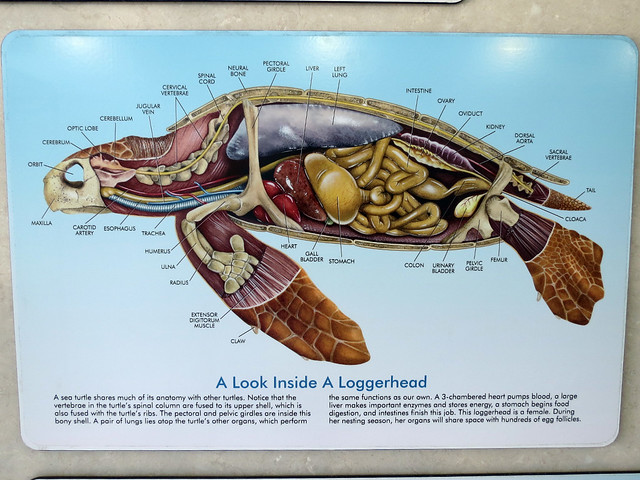

Turtle insides!

Educational tours are offered several times daily. Our tour began with a presentation on the different types of turtles that come to the hospital.

The hospital used to be a nightclub!

Turtle classroom

Next we got to see where injured turtles are admitted and where operations and procedures occur. We could see that the patients can be quite large!

Turtle hospital operation room

The biggest patient ever admitted to the hospital

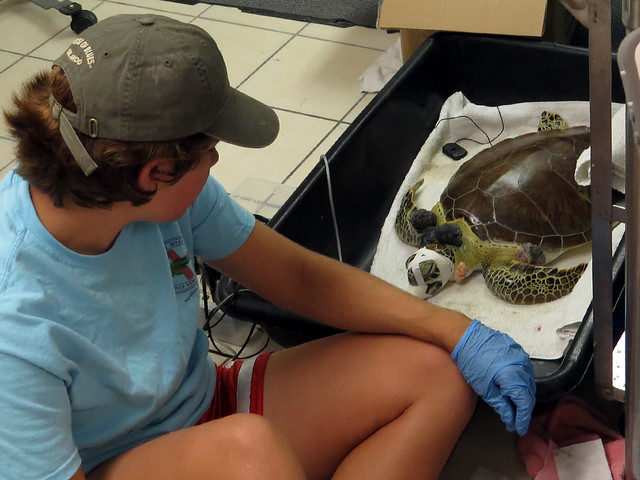

A turtle was recovering from a procedure when our tour came through. A member of the staff must stay with any turtle as it comes out of anesthesia to help it breathe — unconscious turtles don’t breathe on their own.

A patient recovers from anesthesia

We learned about the rehabilitation pools. The original sea water pool houses permanent residents as well as turtles at the last stage of rehab before release. Today the facility also has additional smaller tanks that can house turtles at various stages in their rehabilitation.

Map of the turtle rehabilitation tanks

Rehabilitation tanks

We learned about some of the patients. Jack was a Green Sea Turtle with the condition Fibropapilloma Virus. This may manifest as large growths, which can be seen on Jack’s front left flipper in this photo.

Jack

Xiomy was a Loggerhead Sea Turtle that was found in Islamorada as the victim of a boat strike. She had been admitted on July 29th, 2013. Xiomy was released in October.

Xiomy

We were surprised to learn that the hospital had an education turtle in residence. Zippy the Educational Ambassador is a Loggerhead Sea Turtle that came to the Hospital from Gumbo Limbo on July 28th, 2013. Florida Atlantic University has a research facility at the Gumbo Limbo Nature Center; hatchling turtles are studied and then released. Zippy was kept to be an education ambassador; if I understood correctly, Zippy will eventually also be released back into the wild (with a very big head start!).

Hi Zippy!

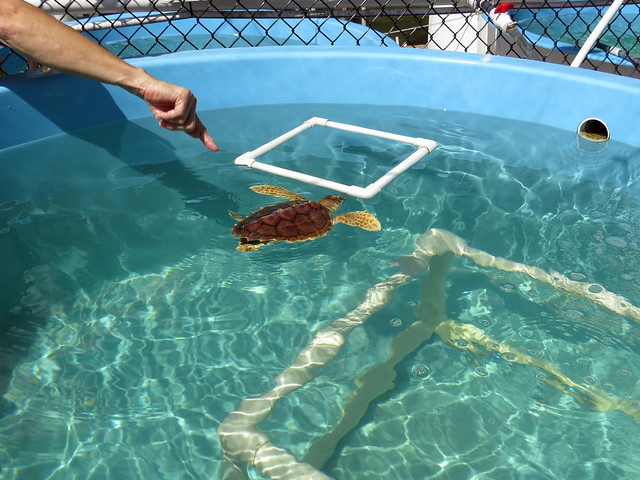

Zippy’s tank includes interesting objects for enrichment

A few little hatchlings were in one of the tanks. These healthy little turtles would soon be released.

Loggerhead on the left, Green on the right

Finally we spent some time looking at the large pool, where we could see healthy turtles nearly ready for release as well as the hospital’s permanent residents.

Sea water pool

Rehab patients nearly ready for release

A patient in the final stages of rehab before release

The hospital has capacity to care for adult sea turtles that are no longer able to survive in the wild due to their injuries. Note the three round masses on the back of turtle in the lower right of the below photo. Those are weights; the turtle is unable to properly regulate its buoyancy on its own. Another turtle in the photo has one weight on its back.

Permanent resident sea turtles

We had a great time visiting The Turtle Hospital, and seeing the great work they do there. They have released over 1000 rehabilitated sea turtles back into the wild since 1986. Sometimes they invite the public to release events — they just released two turtles on February 14th. Keep an eye on The Turtle Hospital Facebook page to keep up with the latest news.